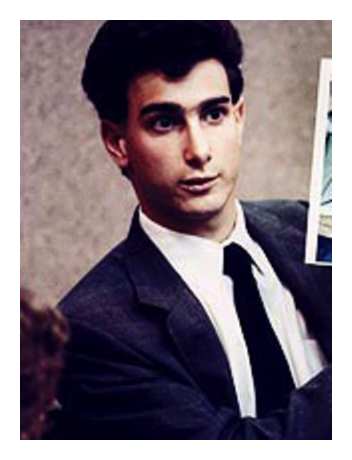

The Exonerated: Marty Tankleff

The wrong man? Questions linger about 1988 murder case

By John Springer, Court TV, Feb. 4, 2002

Retired New York insurance broker Seymour Tankleff bid goodnight to members of his weekly high-stakes poker game and settled down to paperwork in the study of his expansive home overlooking the Long Island Sound.

It was 3 a.m. on Sept. 7, 1988, when the last of the "After Dinner Club" players departed the 5,000-square-foot ranch-style home Tankleff shared with his wife and 17-year-old son, Marty, in the exclusive North Shore enclave of Belle Terre, N.Y.

Tankleff, 62, was commissioner of constables for the incorporated village but had few official duties. Belle Terre, which means "beautiful land" in Latin, was known not for crime but rather for its million-dollar homes located at the end of long, winding driveways leading into the woods.

Belle Terre proved not to be a safe place to live, however - at least not for Tankleff and his 53-year-old wife, Arlene. Sometime between 3 a.m. and 6 a.m., someone savagely bludgeoned Seymour and Arlene Tankleff and then slit their throats.

Marty Tankleff, who was to supposed to begin his senior year of high school that Tuesday morning 13 years ago, whimpered "someone murdered my parents" when the first police officers arrived in response to his 911 call at 6:10 a.m. Marty told the operator that he awoke to find his father alive but "gushing blood" from a neck wound. Arlene Tankleff, who was nearly decapitated, was already dead when she was found in the master bedroom on the opposite end of the house.

Within minutes of the arrival of investigators, Marty told police that he knew who most likely was behind the killings: Jerry Steuerman, his father's business partner in a chain of bagel stores and the last person to leave following the poker game. Steuerman and Seymour Tankleff had been having a dispute about the bagel stores for about 10 weeks. Arlene Tankleff had expressed fears two weeks earlier that Steuerman was capable of violence, Marty told two homicide detectives.

Veteran homicide Det. K. James McCready, one of a long line of McCreadys to become Suffolk County cops, was interested in what Marty was telling him about Steuerman but was more interested in hearing Marty's story. The youth voluntarily accompanied detectives to police headquarters for an interview.

Marty's Story

According to a 14-page police report, Marty told McCready and partner Norman Rein that he showered and kissed his mother goodnight about 11:15 p.m. the night before the killings. Marty awoke about 5:35 a.m. but lay in bed until 6:10 a.m., when he got up, turned on the bedroom light from the wall switch and prepared for his first day at Earl L. Vandermuelen High School in nearby Port Jefferson.

Marty told McCready and Rein that he then he noticed that the lights were still on in the house and he went to investigate. The master bedroom was dark and there was no sign of anyone there, so Marty went to his father's office and discovered Seymour Tankleff severely injured.

Using a phone in the office, Marty placed the 911 call, according to the police account of the interview. Marty then followed the operator's instructions, grabbing a clean towel and placing it over the wound. Marty told McCready that his hands were covered with blood when he opened a door to the garage to see if his mother's car was there - it was - and when he used a kitchen phone to call his step-sister and a friend from school who was expecting a ride.

Having already walked through the Tankleff home, McCready was suspicious. Why, he wanted to know, was there no blood on the doorknob to the garage nor the phone in the kitchen? And why was there blood on the light switch in his room if he had turned it on when he first awoke?

Marty did not have any answers that satisfied McCready, so he tried something controversial but that already had the stamp of approval from the U.S. Supreme Court. McCready tricked Marty.

"I stepped out of the room for a moment and caused one of the other extensions in the office to ring. I then answered the telephone in a loud clear voice," McCready wrote in his report. "I then re-entered the [interview] room and told Marty that his father had come out of his comatose state due to the fact that he was given adrenaline ... and said he, Marty, had beaten and stabbed him."

Seymour Tankleff, in fact, still lay hospitalized in a coma at that point. He died 29 days later, never regaining consciousness or identifying his attacker. McCready's deceit, however, had the desired effect. Marty began to wonder aloud whether he could have attacked his parents and not remembered.

"He said whoever did this needs psychiatric help. We then asked him if he thought he needed psychiatric help," the report continued. "He then asked if he could have blacked out and done it ... He said that maybe it wasn't him, but another Marty Tankleff that killed them ... He said he could have been possessed ... He said it was starting to come to him."

The Confession

McCready stopped the interview at that point and advised Marty Tankleff of his right to remain silent. Marty, however, was still willing to talk.

He went on to tell the detectives a chilling story of how his displeasure with his parent's constant fighting and his sense of being under his mother's "thumb" became too much for him. Among his complaints were that he was not permitted to play contact sports, he lost his boating privileges and that he was being forced to drive "the crummy old Lincoln" rather than a sportier car. His parents were upset that he did not complete a list of chores.

Most of all, Marty feared what would become of him if his parents, who adopted him at birth, divorced. He acknowledged that if both his parents were dead, he stood to inherit a large amount of money.

Then came the confession. According to McCready, Marty described waking up about 5:35 a.m. attacking his mother first with the bar of a dumbbell from his bedroom. Naked to avoid getting any blood on his clothes, Marty claimed he struck his mother four or five times but she fought back, yelling, "Why?" and "Please help!" Arlene Tankleff fell off the bed and Marty ran to the kitchen and grabbed a knife next to a watermelon, which was then used to cut her throat, according to McCready's account of the confession.

Still naked, Marty hid the bar and knife behind his back as he confronted his father, who was still seated behind the desk in the study where the card game was held.

"What are you doing?" Seymour Tankleff asked Marty, according to the police account of the confession. Marty went on to describe knocking "him silly" with the barbell before cutting his throat.

McCready's report winds down with Marty Tankleff describing how he then washed off blood from himself and the weapons in the shower, and putting the weapons back before getting back into bed. Marty agreed to give a written and videotaped confession but police never got that far.

A phone call from a lawyer ended the interview abruptly and police got all they were going to get from Martin Tankleff, who was booked on two counts of murder.

Case Closed?

Marty Tankleff confessed to killing his parents within hours of the gruesome murders of his adoptive parents, but the case was far from closed. Marty's extended family quickly hired prominent defense lawyer Robert Gottlieb to represent the 17-year-old and Gottlieb moved quickly to get his client freed on $1 million bail.

The confession, the defense contended, was the product of coercion by police detectives anxious to make an arrest and the real killer or killers were on the loose.

Then Jerry Steuerman disappeared mysteriously, after clearing out a joint account he and Seymour Tankleff controlled. Steuerman's 1987 Lincoln Towne Car was discovered near Islip-McArthur Airport about a week after the killings with the keys in the ignition, the engine running and both the driver and passenger doors ajar.

Police said they did not consider Steuerman a suspect but were obliged to look for him. They put a trap on his girlfriend's phone and it paid off 29 days later. Steuerman called his girlfriend from California and mouthed one word: "pistachio." It was their pre-arranged signal to indicate that he was alive and well. Steuerman explained to police that he staged his disappearance and made up stories about receiving death threats because the killings frightened him and he was tired of people looking at him accusingly.

The Tankleff case was getting more bizarre with each passing day. Long Island and New York City newspaper were competing fiercely to break developments and testimony about Marty Tankleff's purported confession as a slew of pre-trial hearings brought more and more attention to the case.

Revelations surfaced about different characters in the case that further twisted the story. Steuerman, the self-style "Bagel King of Long Island," was repaying Seymour Tankleff $2,500 a week toward more than $350,000 Steuerman had borrowed from his partner. Reports surfaced that McCready, who had the reputation of being an effective detective but a bit of a cowboy, had been accused of lying about a suspect's identification in an unrelated murder case in 1985. He claimed it was a mistake - not perjury.

It was against that backdrop that Marty Tankleff went on trial in April 1990. The proceedings in Suffolk County Court in Riverhead were televised almost gavel to gavel by a Long Island cable news station - a full year before Court TV first went on the air.

The Trial

A jury of seven men and five women listened to evidence in the Tankleff case for more than 10 weeks. They heard the 911 operator, neighbors, the poker players - including the mayor of Belle Terre - paramedics and friends of Marty who said he had recently mentioned that he could have any car he wanted if his parents were dead.

The jury also heard numerous forensic witnesses, including police criminologists and hair experts. A blood expert testified that the watermelon knife tested negative for blood and could not be tested for fingerprints. Another witness testified that tissues in Marty's sweatshirt pocket had blood from his mother, although he told police he never approached her body.

There was also testimony that the blood from a print found on the light switch in Marty's bedroom, which had a pattern on it indicative that a glove was worn, came either from Marty or his mother.

The prosecution was more or less forced to call Jerry Steuerman, the business partner, to establish that he was at his daughter's home within 19 minutes of the end of the card game. For three days, Steuerman answered questions about his business dealings, money he owed his partner and his staged disappearance to California.

The defense was trying to establish that Steuerman had more motive than Marty and that the police did next to nothing to investigate the possibility that Steuerman could have been involved. Steuerman had had enough by his third day on the stand.

"I staged the [disappearance] scenario because I did not want to be going through what I have been going through here," Steuerman testified on cross-examination by Gottlieb.

"Three days on the witness stand and I didn't do anything. It is not fair," he said, raising his voice. "It's not fair that I am being put through this and Marty Tankleff, who is accusing me, is not. I am sitting here for three days baring my soul to the world and it is not fair."

Gottlieb tried several times to interrupt but was unsuccessful. Steuerman had a lot to get off his chest and did 13 days into the trial.

"The only mistake I made in my life ... The only mistake is I lived lavishly. I was a poor man living like a millionaire," Steuerman said. "I did a foolish thing [by leaving]. ... but I am no murderer and I should not be here."

Detective Testifies

Before the trial, McCready publicly talked about his dislike for Gottlieb and promised that there would be some heated exchanges. He was right.

Prosecutor John Collins led McCready through his early suspicion about Marty and his account of the confession.

"The demeanor of the defendant at the time I spoke to him, from the time I first spoke to him, was totally, totally inappropriate," said McCready, who was by then retired. "His emotional response to what was going on in that house - about what had happened to his father his mother - was totally, totally inappropriate."

Gottlieb made much of the fact that Marty was separated from his family and wore no shoes and only a sweatshirt and shorts during what he called his "interrogation" by McCready. He asked the retired detective about his 1985 testimony in the unrelated case that was called into question, all in an effort to show the jury that McCready rushed to judgment about Marty and got a traumatized teen to implicate himself.

"Can you agree that different people react differently to stress?" Gottlieb asked. "As a matter of fact, some people under stress became very calm in dealing with stress. Would you agree that it would be a very stressful situation to find one's father brutally stabbed, detective?"

McCready's answer silenced Gottlieb and the packed courtroom for a full 10 seconds.

"Oh, God I would never want to find my mother and father the way he found his," McCready said. "I think anybody in this room, other than the defendant, would probably be a box of rocks if they found their parents like that."

The Defense

The defense challenged every forensic witness for the prosecution almost point for point, hair by hair. Comparing the confession to crime scene evidence, Gottlieb was attempting to raise reasonable doubt by noting that the police account of Marty's statement did not jibe with the hair and blood evidence.

Gottlieb challenged the police investigation as a sloppy and inept, and accused detectives of rushing to judgment about Marty's involvement in the killings after minimal investigation.

Gottlieb also called a prominent Manhattan psychiatrist, Herbert Spiegel, to testify that Marty was a suggestible teen and was probably experiencing post-traumatic stress when he was being interviewed by police.

The jury was captivated, however, by the first defense witness. Reporters filed into the courtroom after word leaked out that Marty Tankleff would take the stand in his own defense. The move surprised many people. Putting the defendant on the stand is always risky, and one Tankleff juror had already been dismissed after commenting in a bar during the trial that perhaps police had the wrong guy.

"Marty, you have been charged with killing your mother and your father. Did you kill your mother? Gottlieb asked.

"Absolutely not," Marty replied.

"Marty, did you kill your father?" Gottlieb asked.

"Absolutely not," the defendant insisted.

Marty went onto to confirm that he made the incriminating statements attributed to him by McCready during testimony and in the police report. He said the statements, however, were intended to get police to leave him alone so that he could go see his father in the hospital.

McCready's phony telephone call and other things police were saying had Marty wondering if he could have done it, he testified. He said he was troubled by McCready's insistence that his hair was found clasped in his mother's hand and that his father awoke from his coma and implicated Marty.

"They had me believing that was the way it was. I was brought up to trust and believe in cops, and he was saying it as if it was fact," Marty said on the stand. "I felt this was all a nightmare and I would wake up and this would all be over."

The Jury

At the end of testimony, the prosecutor, Collins, asked the jury to apply common sense during their deliberations.

Would someone who was innocent crumble and confess falsely so quickly? Why was Arlene Tankleff's blood on tissues in Marty's pocket if he didn't go near her body? Why wasn't there any blood on the doorknob to the garage and the phones if his hands were full of blood when he searched for his mother?

Finally, Collins asked jurors to ask themselves why Marty Tankleff was still alive and his parents were not.

"Your common sense will tell you that during the early morning hours of Sept. 7, 1988, someone did not just drop out of the sky and commit the savage attacks on Seymour and Arlene Tankleff and leave this defendant blissfully asleep in the room across the hall," Collins said.

Suffolk County Court Judge Alfred Tisch charged the jury and ordered the panel sequestered throughout their deliberations. The jury deliberated for eight days, at the time a record for a Suffolk County jury. Marty, who was still free on bail, paced the corridor outside the courtroom nervously, huddled always with cousins, aunts and uncles who stood by his side throughout the trial. Over a long weekend, he joined journalists watching the courtroom drama "Twelve Angry Men" on videotape.

On June 28, 1990, the jury finally agreed on a verdict. Marty Tankleff rose from his chair.

He winced when the jury found him guilty of the depraved indifference murder of his mother. He rested his head on the defense table after being convicted of intentional murder for the killing of his father.

McCready commented that it was first time he had seen Marty Tankleff cry. Several jurors said the defendant's lack of emotion during his testimony coupled with physical evidence led to their decision to convict, despite their lack of confidence in the police investigation and dislike of McCready and Steuerman.

One juror quickly reversed course, saying publicly that he was brow-beaten by another juror into voting guilty. The defense seized on several juror and prosecutorial misconduct charges but the convictions held up.

Not Over Yet

Marty Tankleff was sentenced to 50 years to life in prison and is serving his time at the Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, N.Y. He will be 69 years old before he can even apply for parole.

Although he has exhausted every possible trial-related appeal to state and federal courts, Tankleff, now 30, has not given up and still maintains his innocence.

"I'm innocent. I am innocent," Tankleff insisted in an interview for a Court TV documentary on the case airing Feb. 6 at 10 p.m. "It wasn't me. I loved my parents. I would never hurt them."

Long Island private investigator Jay Salpeter, a retired New York City police detective, believes Tankleff and is investigating leads which he says the Suffolk County District Attorney's Office refused to investigate. He declined to disclose what those leads were but believes that, if proved, they could become form the basis for a new trial motion.

"This kid is innocent. Marty doesn't have a motive. The motive goes with Steuerman," Salpeter told Courttv.com. "Suffolk County police have a history of not being able to solve a murder case unless they have a confession or an eyewitness. We saw evidence of an intruder that they did not see."

Collins, the prosecutor, said he convicted the killer of Seymour and Arlene Tankleff and has seen no evidence to suggest otherwise.

"I have been involved in a number of cases over the years and some of them have continued to pursue all available remedies available to them under the state and federal law. I think money and the fact that there are some devoted family members still willing to pursue the cause makes this case somewhat different than the others," said Collins, now chief of the homicide bureau of the Suffolk County District Attorney's Office.

Gottlieb, a former Manhattan prosecutor who ran twice for Suffolk District Attorney and lost, said he is still troubled by the convictions and believes his client was not only innocent, but that the prosecution did not meet its burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

"I never understood the verdict. I never thought the verdict was supported by the evidence, which means if Marty didn't do it someone else did," Gottlieb said. "The task has always been to uncover who that other person or persons are ... Without never evidence, it is becoming more and more difficult to free Marty."

Tankleff's appeals lawyers fell one judge shy of winning a new trial when a federal court ruled 2 to 1 that the defendant was probably warned by detectives before he confessed. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal of that ruling two years ago, leaving pro bono appeals lawyer Steven Braga of Washington, D.C., with just two options.

Braga said he will make a motion this spring that Tankleff had "ineffective assistance of trial counsel." He could also request clemency from Gov. George Pataki on the grounds that Tankleff was wrongly convicted, which he acknowledges is a long shot.

| ||||

The Exonerated: Marty Tankleff

an organization working to correct wrongful convictions

Injustice Anywhere